Written by:

Why is it important to integrate behavioural aspects in passive (road) safety research?

Understanding human behaviour is essential to improving passive (road) safety. Passive safety measures, such as vehicle design features or personal protective equipment, can only deliver their full safety potential if people actually use them, use them correctly, and use them consistently.

Behavioural theory helps explain why this is not always the case. By integrating behavioural theory into passive safety research, researchers can better identify the barriers and enablers that shape safety-related behaviour. This knowledge supports the development of vehicles, protective equipment, and road environments that align more closely with how people behave in practice than with how they are expected to behave in theory.

💡For example, a seatbelt worn incorrectly, a helmet not used or poorly fitted, or a car seat improperly adjusted can significantly reduce protection in a crash. Similarly, for cyclists or e-scooter riders, whether and how protective equipment is worn can completely change the outcome of a crash.

In this sense, behavioural insights can inform more user-oriented design approaches, helping ensure that passive safety solutions better match user needs and behaviours and maximise their safety potential. For policy, behavioural evidence supports approaches that go beyond regulation alone, helping shape communication, incentives, and supportive environments that make safer behaviour easier and more acceptable for road users.

What kinds of frameworks or models can we use to explain road user behaviours in passive safety research?

Researchers and practitioners frequently use behavioural theories and models to identify the factors influencing intention to perform a behaviour or actual behaviour.

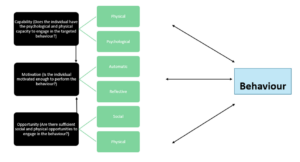

One of these models is the COM-B. The COM-B model can be used for behavioural diagnosis to understand what needs to change for a behaviour to occur. Its basic premise is that an individual needs to have the capability, opportunity and motivation to engage in a given behaviour:

- Capability refers to the individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the behaviour, including having the necessary knowledge, skills, and physical ability.

- Opportunity encompasses all external factors that make the behaviour possible or prompt it, including both the physical environment (e.g. resources, time, infrastructure) and the social environment (e.g. social norms and influences).

- Motivation includes all internal processes that direct behaviour, incorporating both reflective processes (e.g. conscious intentions, beliefs) and automatic processes (e.g. emotions, impulses, habits).

Source: Adapted from Mitchie et. al (2011)

An additional benefit of this model is that it sits in the core of the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW), a framework developed to support the design and evaluation of behaviour change interventions. COM-B can be found at the centre of the wheel, identifying the influences of behaviour. Surrounding and linked to the core, the next layer of the BCW consists of intervention functions (such as education, training, persuasion, and environmental restructuring). The outermost level demonstrates the policy categories (i.e. regulation, communication and marketing, service provision).

Although the COM-B is not derived from a single psychological theory, the model is holistic and practical as it supports the design of behaviour change interventions, and therefore applicable across domains (i.e. public health, transport, sustainability).

💡In the context of passive safety research, the framework can be applied by researchers and practitioners in many problems that require an in-depth understanding of users´ behaviour and the systematic identification of interventions that can effectively address these issues. For example, researchers have used the COM-B model to examine barriers to correct child restraint system use.

How is IMPROVA applying behavioural theory in passive safety research?

Within IMPROVA, behavioural science is applied to better understand how people interact with passive safety solutions across the road safety system, with a primary focus on pre-crash behaviour. In particular, the project examines how vulnerable road users own, use, and perceive personal protective equipment, as these behaviours directly influence the real-world effectiveness of passive safety and the severity of injuries sustained in a crash.

IMPROVA also recognises that behaviour continues to play a role after a crash has occurred. This includes, at a general level, how people engage with emergency response systems, how first responders apply established protocols under real-world conditions, and how individuals navigate rehabilitation and long-term recovery. These post-crash processes can influence injury outcomes and long-term consequences (LTC), as well as shape future safety behaviour and risk perception.

While these post-crash behavioural aspects are not analysed in detail within the project, they are acknowledged as part of the wider context in which passive safety operates. IMPROVA therefore applies behavioural insights where they add the greatest value, strengthening passive safety research with a clear focus on reducing injury severity and long-term consequences for vulnerable road users in real-world conditions.

How is IMPROVA using behavioural science to explore the barriers to PPE ownership and uptake among VRUs?

IMPROVA investigates PPE ownership and use among VRUs through (1) a structured literature review and (2) a behaviourally informed survey run in five European cities (Athens, Barcelona, Copenhagen, London and Rome). The survey captures not only whether people own PPE and how often they use it, but also why, including barriers, motivations, and context of use across motorcyclists/moped riders, cyclists and e-scooter riders.

Additionally, the survey also explores attitudes towards less familiar/innovative PPE, such as airbag or inflatable helmet concepts for cyclists and e-scooter riders, and motorcycle jackets/trousers with novel or inflatable protection (and other emerging protective solutions). This will allow IMPROVA researchers to understand not just current behaviour, but also the potential for early adoption, including perceived benefits and barriers such as availability, price, comfort, practicality, and trust in the technology.

The COM-B was utilised in the survey to examine the factors underlying the non-purchase or non-use of PPE among VRUs. Building on existing evidence on this topic and hypotheses around factors influencing PPE uptake derived from the COM-B model, the survey was designed to capture a comprehensive range of barriers influencing PPE adoption. By structuring questions around capability, opportunity, and motivation, IMPROVA sought to holistically diagnose the behavioural drivers of PPE adoption and to identify targeted, evidence-based interventions capable of promoting both increased ownership and more consistent use of protective equipment.

What key insights has IMPROVA uncovered so far about PPE use among vulnerable road users?

In the case of motorcyclists, PPE ownership rates were high. However, an in-depth examination of use of protective jackets shows that consistent use remains low, particularly among urban and short-trip riders. Barriers include discomfort in hot weather, perceived low risk in short trips or in urban areas, cost, limited knowledge and inconvenience, highlighting the need for integrated interventions combining persuasive communication, training to help users find the right jacket, economic incentives, and product innovation to design ergonomically improved and climate-appropriate gear. Persuasive communication campaigns should address the underestimation of risk when riding short distances.

Motorcyclist riding a bike with a helmet on.

As far as cyclists are concerned, about 22% reported owning no PPE. A common factor discouraging helmet purchases was the habit of riding without safety gear. Interventions to nudge cyclists into purchasing PPE can include offers by retailers such as “helmet included automatically with new bike purchases”, changing the context of the purchasing decision so that the default is owning PPE. Social norms heavily influence behaviour, particularly in cities where riding without gear is perceived as the default. Helmet use is inconsistent even among owners, with common deterrents including assumptions about low risk in short trips or for low frequency riding, forgetfulness, the inconvenience of carrying around equipment, thermal discomfort, and aesthetic concerns. Survey results suggests that helmet behaviour among cyclists is strongly shaped by local cycling culture and sociodemographic characteristics.

A bicyclist riding a road bike with a helmet on.

E-scooter riders show mixed PPE ownership patterns, with frequent riders and those using e-scooters for delivery work demonstrating higher usage.

Two guys riding a e-scooter without a helmet on

Automatic and reflective motivation barriers, including habits and the belief that PPE is not necessary due to low-frequency riding, deterred e-scooter users from purchasing safety gear. The main barriers to consistent helmet use resembled those identified among cyclists. Interventions should include the integration of helmets with long-term subscription models (for shared e-scooters), app-based reminders about helmets before unlocking a shared e-scooter, persuasive communication campaigns and modelling interventions presenting helmets as stylish accessories, providing lockers near e-scooter parking zones, or making portable, foldable helmet designs more widely available through partnerships with manufacturers. Collaboration with manufacturers could help diffuse heat-adapted PPE innovations.

Overall, the survey results suggest that across all VRU groups, PPE usage patterns are shaped by a mix of capability, motivation, and opportunity factors, which vary by mode, trip patterns (i.e. frequency or journey purpose), city context, and user segment. Effective PPE promotion must therefore include context-specific strategies. Tailoring measures to local cultures, environmental conditions, trip patterns, and demographics can improve the acceptance of such measures and eventually the adoption of PPE.

Written by Lamprini Papafoti and María Angélica Pérez from FACTUAL.